Why Russian literature must lose its innocence

Germany's "Russia-complex" is linked to an uncritical adulation of Russian literature. The colonial mindset expressed in many Russian classics is too often overlooked.

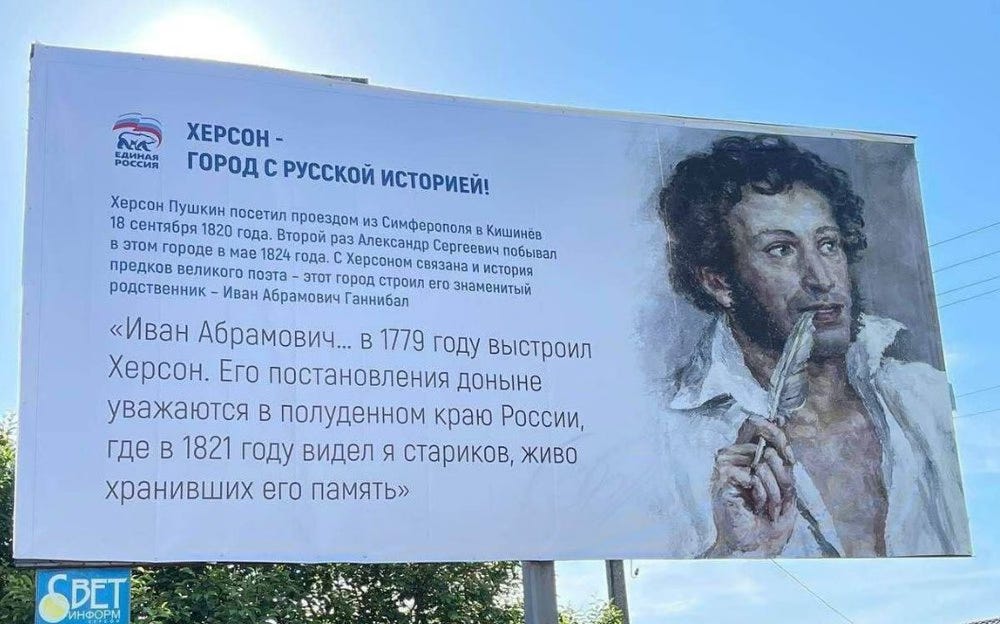

A poster in Kherson during the occupation of the city by Russia. “Kherson - a city with Russian history” next to a portrait of Aleksandr Pushkin

On 27 June 2023, the Russian army fired a missile at a popular restaurant in Kramatorsk, a city in the Donbas not far from the Ukrainian-Russian front. Among the guests that day was Viktoria Amelina, a well-known Ukrainian writer who had been documenting Russian war crimes against the Ukrainian civilian population in the occupied territories since the Russian full-scale invasion. Amelina suffered serious injuries and died on 1 July 2023 in a hospital in Dnipro.

It is not unlikely that the target of the missile attack was deliberately chosen by Russia: the pizzeria was a popular meeting place in Ukraine for journalists, intellectuals, and artists. Russia is waging its war of aggression in a genocidal manner with the aim of destroying Ukraine as a state and nation. Russian authorities have deported thousands of Ukrainian children with the openly declared intention of ‘Russifying’ them. Intellectuals, artists, political elites, and veterans of the Ukrainian army are being systematically persecuted; the Russian army is targeting Ukrainian cultural monuments, archives, and museums. In the occupied territories, the public space and the education system are forcibly Russified.

In this context, Russian literature plays a crucial role. One of the most prominent examples is Kherson, where the Russian occupational regime placed a large poster in the city with a portrait of Alexander Pushkin. "Kherson - a city with Russian history," the poster read, with reference to two stays of the "great poet" in Kherson. A typical response in the West to this political instrumentalization of literature is somewhat defensive: Surely Russian culture cannot be held responsible for the politics of the present-day regime? Russian literature has in itself nothing to do with this war, does it? Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Pushkin, Bulgakov – many Germans not only know these authors, many revere them as great writers, which they undoubtedly were. (I personally can’t bear the writings of Dostoyevsky anymore – but let’s leave the question of their literary greatness to literary scholars.) In general, Russian classical literature of the nineteenth century plays an important role in the Western romanticization of Russia, or, as the historian Karl Schlögel put it, the ‘Russia kitsch’.

The often uncritical adulation of Russian literature and its popularity stands in stark contrast to the ignorance of Ukrainian literature of roughly the same period. Who in the West has heard of the Ukrainian classics? Who has read the national poet Taras Shevchenko, Lesya Ukrainka, or Ivan Franko? Anyone who has tried to find a German translation of the works of any of these writers will know how few, if any, there are available. At the same time, there is a wide choice of different, often beautifully made, editions of Russian classics. The reasons for this ignorance are structural: the colonial dominance of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union in Eastern (Central) Europe went hand in hand with the dominance of Russian culture and the marginalization of others.

Russia’s attempt to eradicate Ukrainian national consciousness has historical precedents. Be it the far-reaching ban on publications in the ‘Little Russian’ (i.e. Ukrainian) language, decreed by the Minister of the Interior of the Russian Empire in 1863, or be it the terror at the beginning of the 1930s, when almost the entire Ukrainian intelligentsia of the Soviet Union was murdered as Ukrainian ‘fascists’ and ‘nationalists’ at the behest of Stalin. Today, these artists are remembered in Ukraine as the Executed Renaissance.

Still, one might argue, this is not the responsibility of Russian authors, many of whom actually opposed the tsarist and later the Soviet regime. It is true that these authors were not responsible for these policies, but this line of argument misses a crucial point: the colonial dimension of Russian literature. For example, in his epos Mazepa, Aleksandr Pushkin denigrates the Ukrainian hetman Ivan Mazepa as a dishonourable traitor and glorifies tsar Peter I (the so-called ‘Great’). It was Peter I who transformed the Muscovite state into a European power and added the self-description Rossiiskaia Imperiia—Russian Empire. In 1991, Joseph Brodsky, winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1987, wrote a poem in response to Ukraine’s declaration of independence in which he showered the country and its people with absurd anti-Ukrainian stereotypes. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the famous and much-respected Russian Soviet dissident and writer, was also hostile towards the idea of an independent Ukrainian nation and was supportive of Putin’s regime until his death in 2008. Russia was a colonial empire for centuries, and this had an impact on its literature. It is high time that Russian literature also lost its innocence in Germany and in the West in general.

In Western debates, the calls from Ukraine to stop promoting Russian culture as long as this war is ongoing are often framed as a problematic call to ‘cancel’ certain authors who are still held in high regard. But, as Viktoria Amelina wrote before her death in 2023, should we in the West really be debating the supposed ‘canceling’ of dead Russian authors while Ukrainian authors are being killed right now? Secondly, why shouldn’t we reflect on how the Western cultural scene contributed to the overlooking of Ukraine and the romanticization of Russia? In democracies, theatres, orchestras, and cultural institutions have the right to decide which authors and themes to put on stage. With freedom comes responsibility. Should not cultural managers be asking how they can contribute to a greater awareness of the marginalized cultures of Eastern Europe while Russia is waging a neo-colonial war?

Kyiv-born Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov depicted Ukrainians as uncultured nationalists in his play The Last Days of the Turbins. In 1932, after numerous personal requests from Bulgakov for support, the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin allowed the resumption of this play in Moscow. It was a popular success, with Stalin himself attending several performances. At that time, Ukrainian writers were already being persecuted. Viktoria Amelina knew Russian literature well. She wrote: “‘Manuscripts don’t burn,’ says the devil in Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita. The devil then turns to his servant, a cat, ‘Come on, Behemoth, let us have the novel.’ Russian manuscripts don’t burn; that might be true. But Ukrainians can only laugh bitterly. It’s imperial manuscripts that don’t burn; ours do.“

This text was initially written for a German cultural institution that was planning to stage a play by a Russian author. Following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the director grew increasingly uneasy about the production and persuaded his colleagues to include this text in the program, hoping to raise awareness of the issue. I submitted the text, and what ensued was a passionate debate within the institution. While many argued that including the text was both important and necessary, the head of the institution disagreed. Ultimately, it was not included.

Thank you, Franziska! The hypocrisy of those in the West who claim to support marginalized and oppressed people, but at the same time defend and promote Russian colonialism by amplifying Russian culture is striking.

Thank you for these important points, Franziska! I have to explain these things to many of my European friends, even those who 100% support Ukraine, but still admire Russian literature and can’t get over it.