Germany, Ukraine, and the Fall of Communism in Europe

Witnessing the Day of Germany Unity from Ukraine as a German felt... just bizarre

I am writing this on October 3 in my hotel room in Lviv. I am a German historian of Eastern (Central) Europe at the University of Munich and came to Ukraine yesterday to be part of the XXXI Lviv book forum which will be held in the city until Sunday. My head is still full of the impressions from the discussions I listened to today. Among them was one with the renowned Ukrainian journalist and publicist Vitalii Portnikov about the impact Russia’s full-scale invasion was having on writers. Portnikov is known for his sharp intellect, his irony which sometimes turns into sarcasm. Today he remarked on stage that he disagreed with those of his fellow citizens who say that Ukraine has no choice but to fight against Russia. We do have a choice, he declared. We have the option to become part of Russia, to become part of a state with an atomic bomb which no other state is going to attack - it will be just like in the days of the Soviet Union (Portnikov is 57). But we will lose our freedom, Portnikov continued. I want us to fight for our freedom, not for territory, but for Ukrainian civilization. We Ukrainians are in a very different position than those anti-Putin Russians who dream of a wonderful Russia of the future (which is never going to come). We already have the Ukraine of the future; we have built it. Now, we have to defend it.

I also listened to a discussion between historian Andrii Pavlyshyn and translator Oles Herasym. They discussed how “nazism had been reborn in the 21st century” by presenting a book by the Polish journalist Antoni Sobański (1898-1941) which Herasym had recently translated into Ukrainian. Sobański visited Germany shortly after the Nazis’ ascent to power and published a series of articles in his book “A Civilian in Berlin” in 1934 where he acutely observed the building of a totalitarian state. For Pavlyshyn and Herasym (and for the audience) the parallels to today’s Russia were obvious: the militarization of society, the atmosphere of fear, the reactionary gender roles, the squashing of the free press to name just a few.

But the festival’s highlight today was the poetry reading in the evening. Poets from different countries - from Wales, Israel, New Zealand, Germany, Poland, and Ukraine - shared the stage for a bilingual (sometimes trilingual) reading of their poetry, with many poems dealing with Russia’s war against Ukraine. This was an event of international solidarity, a space for mourning of Ukrainian writers who have perished at the frontline, a sharing of the traumatic experiences of war. Poetry can perhaps express such emotions in a way no other literary form can. But it was also a celebration of Ukrainian culture, its place in the world. Tellingly the name of this poetry reading was simply “for the future”. For all the sadness, the mourning in the room, I - as an outside observer - also sensed a feeling of hope, of resilience, of dignity. Yes, we are wounded, but we have not been defeated, nor will we be.

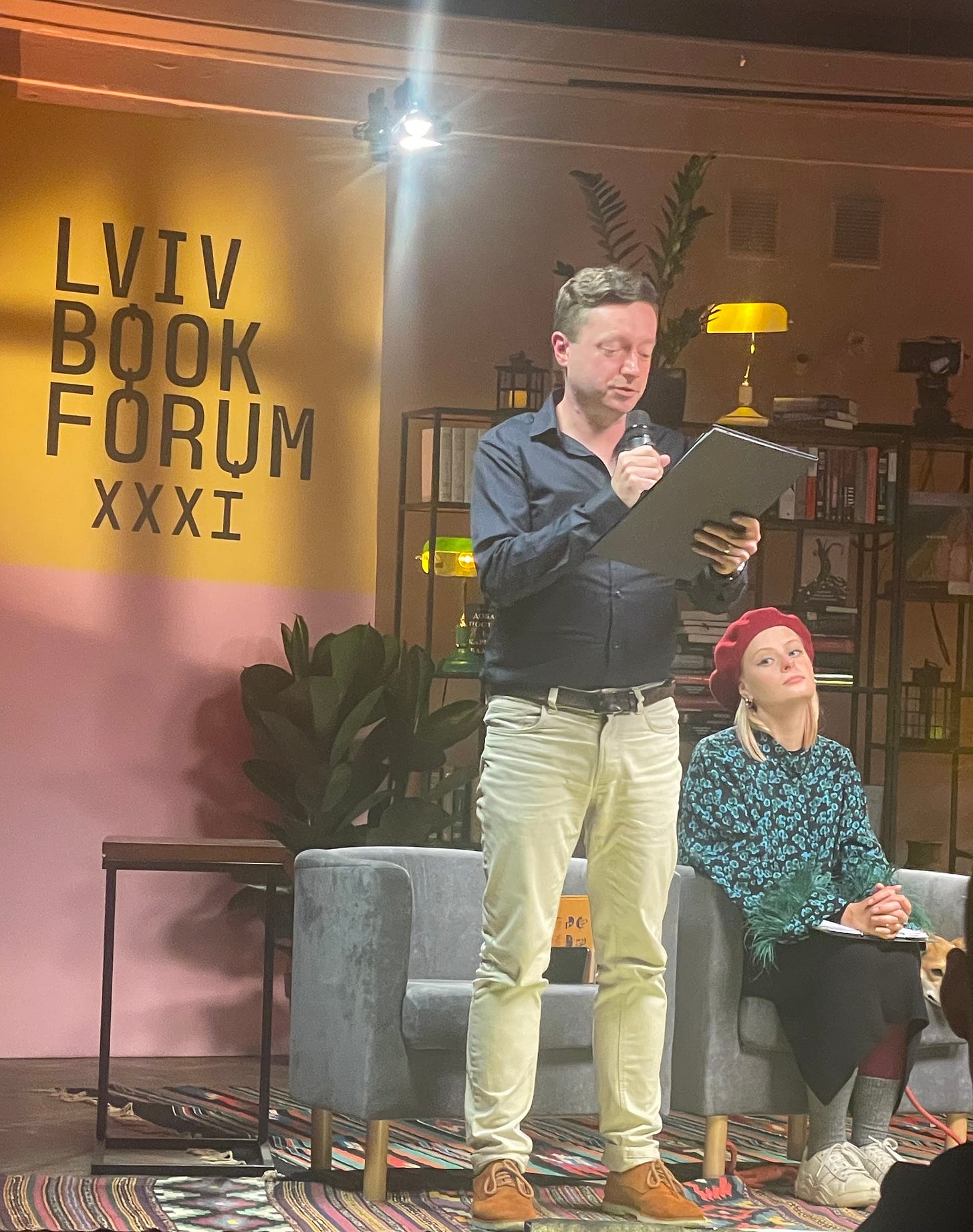

Ukrainian poet Ostap Slyvynsky reading one of his poems at Lviv Book Forum, 3rd of October 2024.

While this was my day in real life in Lviv, the news on my phone and on my social media feed on X were completely different. In a private chatgroup of supporters of Ukraine, appalled messages about a grotesque “Demonstration for Peace” taking place today in Berlin kept coming in. On the day of German Reunification an alliance of pro-Russian politicians, media figures, conspiracy theorists and a handful of scholars had called for “No to war and armament! Yes to peace and international solidarity!” Their vision of “solidarity” entailed ending Germany’s solidarity with Ukraine and reaching out to Russia. It was not Russia which figured as an aggressor in the speeches at the rally, but the “West”, America, NATO and the German government. When Ralf Stegner - member of the German parliament for the Social Democrats who had been widely criticized for his participation in the demonstration - took to the stage and pointed out that Russia had attacked Ukraine, he was booed by the crowd. This rendered all his previous justifications for sharing a stage with pro-Kremlin groups absurd. This was not a demonstration for “peace” by any stretch of the imagination. This was a gathering of the authoritarian and anti-democratic forces in Germany some of whom openly repeated Russia’s genocidal propaganda: “The only way to peace in Ukraine is, like 79 years ago, through a complete annihilation of the Nazis. Stop the delivery of weapons to Nazis. Denazify the whole of Ukraine.” read one sign, held by a smiling man with the national flag of Russia pinned to his coat.

It is somewhat unfair to compare the atmosphere at Lviv’s book forum where some of the most brilliant minds of Ukraine come together with this farce of a “peace demonstration” held in Berlin on the same day. And yet it got me thinking. Where does German society stand with regard to the reckoning with its authoritarian past? How can it be that the organizers of this demonstration managed to hijack central spaces of Berlin on the Day of German Reunification and in effect call for the participation, destruction even, of another country in Europe? How can it be that the most visible, even if depressingly small, counterprotest against this grotesque display was not organized by Germans, but by the Ukrainian diaspora in Germany, namely Vitsche, an organization which has become a vital voice against pro-Russian disinformation since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine?

While support for Russia is not solely a phenomenon of Eastern Germany, that is the former GDR, it is hard to overlook that in these regions authoritarianism and sympathies for Russia are stronger than in other regions of Germany. The star of demonstration in Berlin was Sahra Wagenknecht, born and raised in the GDR, who was one of the most prominent members of the Left party (“Die Linke”) until she founded a new party “Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht” (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, BSW) a few months ago. BSW is a populist party, which takes up talking point both of the extremist right and combines it with leftist slogans. It is also known for its pro-Russian statements.

In recent elections in these regions on state level (Bundesland) Wagenknecht’s party as well as the far-right, equally pro-Russian party “Alternative for Germany” (AfD, Alternative für Deutschland) were hugely successful: In Saxony the AfD nearly got exactly the same share of the votes as the Christian Democratic Party (CDU): 34 percent. Wagenknecht’s alliance managed to secure over six percent of the votes, even though this was the first time that the party participated in the elections. In Thuringia, the picture is even worse: the neo-Nazi party AfD was by far the strongest party with 32,8 percent of the votes and the BSW with 15,8 percent got more votes than the parties governing in Berlin (Social Democrats, Liberals, Greens) combined. Considering that the Saxonian Prime Minister Michael Kretzschmer (CDU) is also known for his Russia-friendly statements, it is safe to say that in Thuringia and Saxony up to half of the voters opted for parties with pro-Kremlin positions.

As a historian, this puzzles me. When trying to explain the naivety of Germans towards Russia up to 2022 and even beyond, their longing for “good” relations with Russia at the expense of the peoples of Central Eastern Europe, I often point to the fact that Germans, historically, know Russian imperialism from the position of a partner, not from the position of the victim or from the position of resistance. A joint Russian-German imperialism profoundly shaped the history of Europe from the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at the end of the eighteenth century to the pact between Hitler and Stalin in 1939 to occupy Eastern Central Europe together. But in Eastern Germany, this line of argument does not really work. Do not Eastern Germans know Soviet style dictatorship, Soviet-Russian imperialism? Have they forgotten what it means to live in a dictatorship which only ended in 1990?

And here is where the comparison with Ukraine comes in. Ukraine became independent in 1991. From the 1990s onwards political and intellectual debates in Ukraine about its self-understanding as a nation were inextricably linked to the legacies of communist dictatorship, to a reckoning with the Soviet past. Subjects which had previously been a taboo or had only been discussed since the late 1980s were now in the open with the Holodomor, the artificial famine caused by the Soviet regime in the 1930s being the most painful trauma. To be sure, this reckoning was met with resistance as parts of society and politicians rejecting a clear break with the traditions of the Soviet Union for decades. While in Western Ukraine statues of Lenin already fell in the 1990s, a wave of “Leninopad” (the demolition of monuments to Lenin) only gathered momentum in Central and Eastern Ukraine in the wake of the Revolution of Dignity in 2013/14. The question of “decommunization” became a political and societal issue - well before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022.

Such a wide-ranging reckoning with the Soviet legacy never took place in Eastern Germany. The re-invention of Eastern Germany as a new Germany in the way that Ukraine re-invented itself in the 1990s and 2000s did not take place. Why not? For one, Soviet crimes in Ukraine had a different dimension in comparison to Eastern Germany which was not itself part of the Soviet Union, but only of the so-called Eastern Bloc. There was no genocidal violence on the scale of Holodomor in Eastern Germany, nor did the Soviet Union ever attempt to “de-Germanize” the people of the GDR through Russification. Secondly, Eastern Germany could not reinvent itself as a new German nation, because the German nation state already existed in form of Western Germany. Thus, the story of the 1990s is not remembered as a story of national self-liberation and a successful anti-colonial struggle, but as a take-over by the West. Comparisons with Western Germany, unequal wages, the injustices of capitalism overshadowed any notion of what had nonetheless been gained: freedom.

In contrast, in Ukraine the 1990s and the 2000s continued to be marked by a societal struggle for democracy and freedom. While after the reunification of Germany, fighting for free and fair elections was no longer necessary for East Germans (the reunification had secured them), in Ukraine the struggle against the long shadow of the totalitarian past continued. The building of civil society continued; the self-empowerment of citizens continued. Twice Ukrainians took to the streets to fight against anti-democratic back lashes: in 2004 during the Orange Revolution and in 2013/14 in what would become known as the Revolution of Dignity. In Eastern Germany, many people who might have empowered civil society left for Western Germany.

When speaking in Dresden in Eastern Germany in May 2024 I witnessed a telling exchange between an East German and a Ukrainian, both roughly the same generation, both had lived in a dictatorship. The German had obviously been angered by what I had said on the podium - that Germany must deliver more weapons to Ukraine. “Why can’t they (i.e. Russians and Ukrainians) just stop fighting? Like we (presumably Eastern and Western Germans) did in 1990?” “That is a question for Vladimir Putin,” I snapped back. “Russia is responsible for this war, it could stop any time and the war would be over.” This was the point at which a Ukrainian gentleman from the audience got involved, whom I knew to be Ihor Zhaloba, a history professor from Chernivtsi who had gone to the front after the full-scale invasion (aged 58) and became well-known for continuing to give his lectures to students from the trenches at the front on-line. “We will not lay down our weapons.” he declared to the cheers of other Ukrainians (and Germans) in the audience. “We are fighting for our freedom, our democracy, we are fighting for a future for our children in freedom and dignity.” He continued: “I am so glad that we Ukrainians did not have a West Germany to support us. I am so glad that we did not get any Willkommensgeld (“Welcome Money” given to East Germans who came to Western Germany), because it helped us to understand the value of freedom and democracy. We understood that it does not come for free, you have to fight for it, protect it.”

Before I left for the poetry reading in Lviv today, I went to a restaurant at Rynok Square. The waiter complimented me on my “lovely” Ukrainian (which I liked) and asked where I came from. From Germany, I replied. Oh, he said, Germany! How nice! You are very welcome! I did not feel like I deserved such a reaction.